Wynn Las Vegas forfeits $130M in San Diego settlement

|

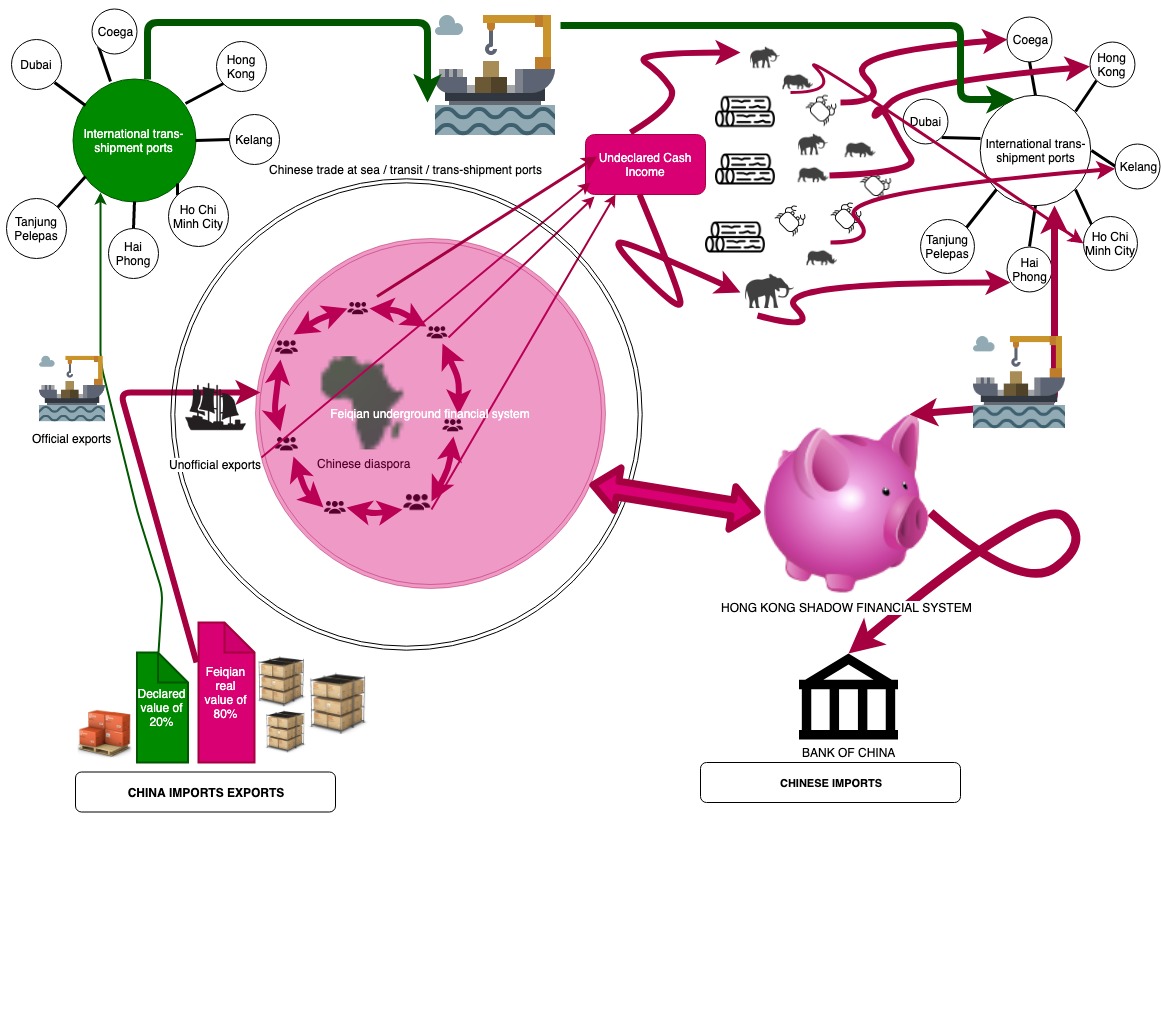

| Chinese "Flying Money" or "qian chen" (钱程 in Chinese characters) leaves little trace for Authorities to track multifarious illegal activities - in this case gambling. |

Wynn Las Vegas forfeits $130M in San Diego settlement

Here is a more comprehensive explanation of the prosecution, charges, and settlement based on this official press release from the U.S. Department of Justice.

Who was being prosecuted:

Wynn Las Vegas (WLV), a casino and subsidiary of Wynn Resorts, Limited.

What they were being prosecuted for:

1. Conspiring with unlicensed money transmitting businesses worldwide to transfer funds for the casino's financial benefit.

2. Facilitating illegal financial transactions that allowed foreign gamblers to evade U.S. and foreign laws governing monetary transfers and reporting.

3. Knowingly allowing and facilitating schemes such as:

- Using independent agents operating as unlicensed money transmitting businesses

- "Human Head" or "Human Hat" gambling

- "Flying Money" or "qian chen" transactions

4. Conducting financial transactions for patrons linked to criminal activities without proper scrutiny or reporting.

The settlement:

1. Wynn Las Vegas agreed to forfeit $130,131,645.

2. This is believed to be the largest forfeiture by a casino based on admissions of criminal wrongdoing.

3. WLV entered into a Non-Prosecution Agreement, which allows them to avoid criminal prosecution in exchange for meeting certain criteria.

Potential penalties if no settlement was reached:

While not explicitly stated, the potential penalties without a settlement could have included:

1. Criminal prosecution of the casino as an entity.

2. Potentially larger financial penalties.

3. Damage to the casino's reputation and ability to operate.

4. Possible criminal charges against individual executives or employees involved in the schemes.

The press release also mentions that 15 other defendants related to this investigation have previously admitted to various crimes, including money laundering and unlicensed money transmitting, with associated criminal penalties exceeding $7.5 million.

This case involved multiple investigating agencies, including Homeland Security Investigations, IRS-Criminal Investigations, and the Drug Enforcement Administration, highlighting the seriousness and complexity of the alleged criminal activities..

How Big

Based on the information provided in the press release, we don't have a specific figure for how much Wynn Las Vegas (WLV) profited from these illegal operations. The press release doesn't provide a comprehensive total for the volume of financial transactions involved either. However, it does give us some partial figures that hint at the scale of the operations:

1. Total forfeiture:

WLV agreed to forfeit $130,131,645. While this doesn't directly indicate their profit, it suggests the scale of the illegal activities was significant.

2. Juan Carlos Palermo's operations:

- Conducted more than 200 transfers with bank accounts controlled by WLV or associated entities.

- These transactions exceeded $17.7 million in total value.

- They were on behalf of more than 50 foreign casino patrons.

3. Individual transactions mentioned:

- In 2018, WLV facilitated financial transactions worth approximately $1.4 million for one individual with suspicious connections.

- Another instance involved "transactions involving millions of dollars" by an individual with a criminal history in China.

4. Other defendants:

- 15 other defendants related to this investigation have previously admitted to various crimes.

- These cases had associated criminal penalties of over $7.5 million.

5. Time frame:

While not explicitly stated, the activities seem to have occurred over several years, as some examples date back to at least 2016.

It's important to note that these figures represent only a fraction of the total volume of transactions involved in the illegal activities. The actual total volume and Wynn's profits from these operations were likely much larger, given the size of the forfeiture and the fact that this is described as "the largest forfeiture by a casino based on admissions of criminal wrongdoing."

Without more specific information, we can't determine the exact profit or total transaction volume. However, the figures provided suggest that the scale of these operations was in the hundreds of millions of dollars, if not more.

Human Head Gambling

Here's a breakdown of "Human Head" or "Human Hat" gambling, which is also known in Mandarin as "人头" or "ren tou". Here's a breakdown of this scheme:

1. Definition: It's a method where one person acts as a proxy gambler for another person.

2. How it works:

- A person, called the "Human Head", purchases chips at the casino (in this case, Wynn Las Vegas).

- This "Human Head" then gambles at the casino, but they're not playing for themselves.

- Instead, they're acting as a proxy for another person who is nearby.

3. Purpose:

- This scheme allows the real gambler (the person directing the play) to avoid conducting financial transactions under their own identity.

- It's used by individuals who, due to federal Bank Secrecy Act or Anti-Money Laundering (BSA/AML) laws, are either unable or unwilling to gamble or conduct financial transactions themselves.

4. Control:

- While the "Human Head" is physically placing bets and handling chips, the true patron (the real gambler) is actually directing the gaming decisions.

5. Casino's involvement:

- According to the press release, Wynn Las Vegas knowingly allowed this form of gambling.

- The casino did not properly scrutinize the true patron's funds.

- They also failed to report this suspicious activity as required by law.

6. Legal issues:

- This practice is illegal because it circumvents laws designed to prevent money laundering and other financial crimes.

- It allows individuals to gamble anonymously, potentially hiding the source of their funds or their gambling activities from authorities.

This scheme essentially creates a layer of obfuscation between the real gambler and the financial transactions involved in gambling, making it difficult for authorities to track the flow of money and potentially allowing for various forms of financial misconduct.

Flying Money

"Flying Money" or "qian chen" (钱程 in Chinese characters) is another illegal money transfer method described in the press release. Here's an explanation of how this scheme works:

1. Definition: It's a method for transferring money internationally, specifically mentioned in the context of moving money between China and the United States.

2. How it works:

a. A money processor, acting as an unlicensed money transmitting business, collects U.S. dollars in cash from third parties in the United States.

b. This cash is then delivered to a Wynn Las Vegas (WLV) patron who otherwise couldn't access cash in the U.S.

c. The patron then electronically transfers an equivalent amount of foreign currency from their foreign bank account to a foreign bank account designated by the money processor.

d. The WLV patron pays the money processor a percentage of the value transferred as a fee for this service.

3. Purpose:

- This method allows individuals to move money across international borders without going through traditional banking channels.

- It's particularly useful for those who can't legally access or move their money into the United States.

4. Casino's involvement:

- WLV knowingly allowed this form of money transfer.

- The casino did not properly scrutinize the source of these funds.

- They failed to report this suspicious activity as required by law.

5. Legal issues:

- This practice bypasses official banking systems and currency controls.

- It avoids scrutiny from financial regulators and potentially allows for money laundering.

- The money processor acts as an unlicensed money transmitting business, which is illegal.

6. Implications:

- This method can be used to evade currency controls, taxes, or to move illicitly obtained funds.

- It makes it difficult for authorities to track the movement of money across borders.

This "Flying Money" scheme is part of a larger pattern of financial misconduct that Wynn Las Vegas was accused of facilitating, allowing patrons to circumvent financial regulations and potentially engage in money laundering or other financial crimes.

This article offers some important context that wasn't present in the Wynn Las Vegas case. Let me summarize the key points:

1. Definition: "Chinese Flying Money" or "Fei Qian" is described as an ancient trade-based settlement system that operates outside the oversight of the formal banking system.

2. Usage in illegal activities:

- It's used as a key enabling financial mechanism for wildlife crime and related smuggling.

- The system allows for billions of dollars to be illegally but invisibly exported from Africa to China.

3. Specific illegal activities mentioned:

- Abalone smuggling from South Africa to Hong Kong via Namibia

- Illegal rosewood harvesting from Angola, Zambia, and the DRC sent to China and Vietnam

- Drugs-for-abalone trade in Western Cape

- A tax fraud case in Namibia

4. Law enforcement challenges:

- The lack of a visible money trail makes it difficult for law enforcement to secure convictions against key organizers of illegal transactions.

5. Investigation details:

- The investigation involved sources from multiple countries including Spain, Hong Kong, Namibia, and South Africa.

- It used court cases, public records, and interviews with law enforcement officials.

This information provides a broader context for understanding the "Flying Money" or "qian chen" transactions mentioned in the Wynn Las Vegas case. It shows that this system is not just used for gambling-related transactions, but is part of a larger phenomenon of informal, untraceable money transfers often used in various illegal activities.

The use of this system in both wildlife crime in Africa and casino-related activities in Las Vegas demonstrates its versatility and the challenges it poses to law enforcement and financial regulators globally.

Prosecutors and Investigators

The specific attorneys involved in the case:

1. Prosecutors:

The case was prosecuted by two Assistant U.S. Attorneys:

- Mark W. Pletcher

- Carl F. Brooker IV

2. U.S. Attorney:

The press release includes a quote from U.S. Attorney Tara McGrath, who commented on the case.

3. Investigating Agencies:

While not attorneys, the press release mentions several law enforcement agencies and their representatives:

- Christopher Davis, acting special agent in charge for HSI San Diego

- Carissa Messick, Special Agent in Charge for IRS-CI in Las Vegas

- Brian Clark, DEA Special Agent in Charge

4. Specific Filing:

The press release doesn't mention a specific court filing by name or number. However, it does refer to a Non-Prosecution Agreement that Wynn Las Vegas entered into as part of the settlement.

The case was handled by the U.S. Attorney's Office in San Diego, as mentioned earlier in the press release. This office falls under the Department of Justice and is responsible for prosecuting federal crimes in their jurisdiction.

Gamblers and Operatives Involved

Based on the information provided in the press release, we can identify some details about the nationalities of foreign gamblers involved and one specific US operator, though the information is not comprehensive. Here's what we know:

1. Nationalities of foreign gamblers:

- The press release mentions gamblers from Latin America and China specifically.

- It states that WLV contracted with "third-party independent agents acting as unlicensed money transmitting businesses to recruit foreign gamblers to WLV."

- The "Human Head" or "Human Hat" gambling scheme is described using its Mandarin name (人头 or "ren tou"), suggesting involvement of Chinese gamblers.

- The "Flying Money" or "qian chen" scheme specifically mentions transfers between China and the United States.

2. Identity of US operators:

- The press release identifies one US operator by name: Juan Carlos Palermo.

- Palermo is described as an independent agent for WLV who operated and controlled multiple unlicensed money transmitting businesses in the United States and abroad.

- Palermo's operations conducted more than 200 transfers with bank accounts controlled by WLV or associated entities, exceeding $17.7 million in total value.

- These transactions were on behalf of more than 50 foreign casino patrons.

3. Other individuals:

- While not named, the press release mentions other individuals involved in suspicious transactions:

- An individual who had been publicly linked to proxy gambling and was denied entry to the United States due to suspected associations with a criminal organization.

- Another individual who had spent six years in prison in China for conducting unauthorized international monetary transactions and violations of other financial laws.

4. Additional context:

- The press release mentions that 15 other defendants related to this investigation have previously admitted to various crimes, including money laundering and unlicensed money transmitting. However, their identities or nationalities are not specified.

While the press release provides some specific information, it does not give a comprehensive list of all nationalities involved or identify all US operators. The focus seems to be on highlighting the methods used and providing examples of the scale and nature of the illegal activities rather than identifying all individuals involved.

Wynn Resorts paying $130M for letting illegal money reach gamblers at its Las Vegas Strip casino

LAS VEGAS -- Casino company Wynn Resorts Ltd. has agreed to pay $130 million to federal authorities and admit that it let unlicensed money transfer businesses around the world funnel funds to gamblers at its flagship Las Vegas Strip property.

The publicly traded company said a non-prosecution settlement reached Friday represented a monetary figure identified by the U.S. Justice Department as “funds involved in the transactions at issue” at the Wynn Las Vegas resort.

In statements to the media and to the federal Securities and Exchange Commission, the company said the forfeiture wasn’t a fine and findings in the decade-long case didn’t amount to money laundering.

U.S. Attorney Tara McGrath in San Diego said the settlement showed that casinos are accountable if they let foreign customers evade U.S. laws. She said $130 million was believed to be the largest forfeiture by a casino “based on admissions of criminal wrongdoing.”

Wynn Resorts said it severed ties with all people and businesses involved in what the government characterized as “convoluted transactions” overseas.

“Several former employees facilitated the use of unlicensed money transmitting businesses, which both violated our internal policies and the law, and for which we take responsibility,” the company said in a statement Saturday to The Associated Press.

In its news release, the Justice Department detailed several methods it said were used to transfer money between Wynn Las Vegas and people in China and other countries.

One, dubbed “Flying Money,” involved an unlicensed money agent using multiple foreign bank accounts to transfer money to the casino for use by a patron who could not otherwise access cash in the U.S.

Another involved having a person referred to as a “Human Head” gamble at the casino at the direction of another person who was unwilling or unable to place bets because of anti-money laundering and other laws.

The Justice Department said one person, acting as an independent agent for the casino, conducted more than 200 money transfers worth nearly $18 million through bank accounts controlled by Wynn Las Vegas “or associated entities” on behalf of more than 50 foreign casino patrons.

Wynn Resorts called its agreement with the government a final step in a six-year effort to “put legacy issues fully behind us and focus on our future.” The SEC filing noted the investigation began about 2014.

It did not use the name of former CEO Steve Wynn. But since 2018, the parent company has been enmeshed with legal issues surrounding his departure after sexual misconduct allegations against him were first reported by the Wall Street Journal.

Wynn attorneys in Las Vegas did not respond Saturday to messages about the company settlement.

Wynn, now 82 and living in Florida, has said he has no remaining ties to his namesake company. He has consistently denied committing sexual misconduct.

The billionaire developer of a luxury casino empire in Las Vegas, Massachusetts, Mississippi and the Chinese gambling enclave of Macao resigned from Wynn Resorts after the reports became public, divested company shares and quit the corporate board.

Last year, in an agreement with Nevada gambling regulators, he agreed to cut links to the industry he helped shape in Las Vegas and pay a $10 million fine. He admitted no wrongdoing.

In 2019, the Nevada Gaming Commission fined Wynn Resorts a record $20 million for failing to investigate claims of sexual misconduct made against him before he resigned. Massachusetts gambling regulators fined the company and a top executive $35.5 million for failing to disclose the sexual misconduct allegations against Wynn while it applied for a license for its Encore Boston Harbor resort. The company made no admissions of wrongdoing.

Wynn Resorts agreed in November 2019 to accept $20 million in damages from Wynn and $21 million from insurance carriers to settle shareholder lawsuits accusing company directors of failing to disclose misconduct allegations.

The Justice Department said Friday that as part of its investigation, 15 people previously admitted money laundering, unlicensed money transmission or other crimes, paying criminal penalties of more than $7.5 million.

Wynn Resorts noted in its statement on Friday that its non-prosecution agreement with the government did not refer to money laundering.

Wynn Las Vegas Forfeits $130 Million for Illegally Conspiring with Unlicensed Money Transmitting Businesses

NEWS RELEASE SUMMARY – September 6, 2024

SAN DIEGO – Wynn Las Vegas, the Las Vegas casino and subsidiary of Wynn Resorts, Limited, agreed today to forfeit $130,131,645 to settle criminal allegations that it conspired with unlicensed money transmitting businesses worldwide to transfer funds for the financial benefit of the casino.

Today’s settlement is believed to be the largest forfeiture by a casino based on admissions of criminal wrongdoing.

“Casinos, like all businesses, will be held to account when they allow customers to evade U.S. laws for the sake of profit,” said U.S. Attorney Tara McGrath. “Federal oversight seeks to prevent illegal funds from tainting legitimate businesses, ensuring that casinos offer a clean, thriving, and safe entertainment option.”

As part of a Non-Prosecution Agreement, which allows a company or individual to avoid criminal prosecution in exchange for meeting certain criteria, Wynn Las Vegas (WLV) admitted that it illegally used unregistered money transmitting businesses to circumvent the conventional financial system.

For example, WLV regularly contracted with third-party independent agents acting as unlicensed money transmitting businesses to recruit foreign gamblers to WLV. For the gamblers to repay debts to WLV or have funds available to gamble at WLV, the independent agents transferred the gamblers’ funds through companies, bank accounts, and other third-party nominees in Latin America and elsewhere, and ultimately into a WLV-controlled bank account in the Southern District of California.

Funds deposited into the WLV-controlled account were transferred into the WLV cage account. WLV employees, with the knowledge of their supervisors, and working with the independent agents, eventually credited the WLV account of each individual patron. The convoluted transactions enabled foreign gamblers at WLV to evade foreign and U.S. laws governing monetary transfer and reporting.

In one example, Juan Carlos Palermo, while acting as an independent agent for WLV, operated and controlled multiple unlicensed money transmitting businesses in the United States and abroad that conducted more than 200 transfers with bank accounts controlled by WLV or associated entities. These transactions, on behalf of more than 50 foreign casino patrons, exceeded $17.7 million.

WLV also facilitated the unlicensed transfer of money through “Human Head” or “Human Hat” gambling, known in Mandarin as “人头” or “ren tou.” In this scheme, a person known as a “Human Head” purchased chips at WLV and gambled at WLV as a proxy for another nearby person who, in some instances, because of federal Bank Secrecy Act or Anti-Money Laundering (BSA/AML) laws, was unable or unwilling to conduct financial transactions or gamble under their own identity. The true patron, however, would direct the Human Head’s gaming. WLV knowingly allowed this form of gambling without scrutinizing the true patron’s funds and without reporting the suspicious activity.

In another example, WLV facilitated the unlicensed transfer of money to and from China through a method known as “qian chen” or “Flying Money.” A money processor, acting as an unlicensed money transmitting business, collected U.S. dollars in cash from third parties in the United States and delivered that cash to a WLV patron who could not otherwise access cash in the U.S. The patron then electronically transferred the equivalent value of foreign currency from the patron’s foreign bank account to a foreign bank account designated by the money processor. The WLV patron paid the money processor a percentage of the value transferred. Like Human Head gambling, WLV knowingly allowed this form of gambling without scrutinizing the source of funds and without reporting the suspicious activity.

WLV also facilitated the international transfer of money and conducted other financial transactions for WLV patrons whose activity should have triggered the filing of Suspicious Activity Reports. For example, in 2018, WLV facilitated financial transactions worth approximately $1.4 million for an individual who two years earlier had been publicly linked to proxy gambling and a year earlier, while in the company of the President of Marketing of a WLV international affiliate, was denied entry to the United States because of suspected associations with a criminal organization.

In another instance, WLV allowed and did not report transactions involving millions of dollars by an individual who, according to publicly available information, had spent six years in prison in China for conducting unauthorized international monetary transactions and violations of other financial laws.

“Of the many unique authorities HSI is able to enforce, understanding and investigating complex financial crimes that lead to holding criminals accountable for their actions, is one that HSI does best,” said Christopher Davis, acting special agent in charge for HSI San Diego. “The success of this investigation is in part due to our partner agencies’ cooperation and dedication to seeing these long-term investigations through to bring justice to these companies and protect American financial institutions.”

“Federal laws that regulate the reporting of financial transactions are in place to detect and stop illegal activities. Deliberately avoiding Bank Secrecy Act requirements is a form of money laundering. IRS Criminal Investigation is committed to following the money and enforcing these laws, wherever it leads” said Carissa Messick, Special Agent in Charge for IRS-CI in Las Vegas.

“Law enforcement put their collective authorities together to ensure the integrity of our financial systems and that they are not circumvented,” said DEA Special Agent in Charge Brian Clark.

As part of this investigation, 15 other defendants previously have admitted money laundering, unlicensed money transmitting, or other crimes, with associated criminal penalties of over $7.5 million.

This case was prosecuted by Assistant U.S. Attorneys Mark W. Pletcher and Carl F. Brooker IV.

INVESTIGATING AGENCIES

Homeland Security Investigations

IRS-Criminal Investigations, Las Vegas Financial Crimes Task Force

Drug Enforcement Administration

Wynn Las Vegas Forfeits $130M for Illegally Conspiring With Unlicensed Money Transmitting Businesses | Homeland Security

SAN DIEGO – Wynn Las Vegas, the Las Vegas casino and subsidiary of Wynn Resorts, Limited, agreed today to forfeit $130,131,645 to settle criminal allegations that it conspired with unlicensed money transmitting businesses worldwide to transfer funds for the financial benefit of the casino. Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) is investigating this case with assistance from IRS-Criminal Investigations, Las Vegas Financial Crimes Task Force, and the DEA.

Today’s settlement is believed to be the largest forfeiture by a casino based on admissions of criminal wrongdoing.

“Of the many unique authorities HSI is able to enforce, understanding and investigating complex financial crimes that lead to holding criminals accountable for their actions, is one that HSI does best,” said Christopher Davis, acting special agent in charge for HSI San Diego. “The success of this investigation is in part due to our partner agencies’ cooperation and dedication to seeing these long-term investigations through to bring justice to these companies and protect American financial institutions.”

“Casinos, like all businesses, will be held to account when they allow customers to evade U.S. laws for the sake of profit,” said U.S. Attorney Tara McGrath. “Federal oversight seeks to prevent illegal funds from tainting legitimate businesses, ensuring that casinos offer a clean, thriving, and safe entertainment option.”

As part of a Non-Prosecution Agreement, which allows a company or individual to avoid criminal prosecution in exchange for meeting certain criteria, Wynn Las Vegas (WLV) admitted that it illegally used unregistered money transmitting businesses to circumvent the conventional financial system.

For example, WLV regularly contracted with third-party independent agents acting as unlicensed money transmitting businesses to recruit foreign gamblers to WLV. For the gamblers to repay debts to WLV or have funds available to gamble at WLV, the independent agents transferred the gamblers’ funds through companies, bank accounts, and other third-party nominees in Latin America and elsewhere, and ultimately into a WLV-controlled bank account in the Southern District of California.

Funds deposited into the WLV-controlled account were transferred into the WLV cage account. WLV employees, with the knowledge of their supervisors, and working with the independent agents, eventually credited the WLV account of each individual patron. The convoluted transactions enabled foreign gamblers at WLV to evade foreign and U.S. laws governing monetary transfer and reporting.

In one example, Juan Carlos Palermo, while acting as an independent agent for WLV, operated and controlled multiple unlicensed money transmitting businesses in the United States and abroad that conducted more than 200 transfers with bank accounts controlled by WLV or associated entities. These transactions, on behalf of more than 50 foreign casino patrons, exceeded $17.7 million.

WLV also facilitated the unlicensed transfer of money through “Human Head” or “Human Hat” gambling, known in Mandarin as “人头” or “ren tou.” In this scheme, a person known as a “Human Head” purchased chips at WLV and gambled at WLV as a proxy for another nearby person who, in some instances, because of federal Bank Secrecy Act or Anti-Money Laundering (BSA/AML) laws, was unable or unwilling to conduct financial transactions or gamble under their own identity. The true patron, however, would direct the Human Head’s gaming. WLV knowingly allowed this form of gambling without scrutinizing the true patron’s funds and without reporting the suspicious activity.

In another example, WLV facilitated the unlicensed transfer of money to and from China through a method known as “qian chen” or “Flying Money.” A money processor, acting as an unlicensed money transmitting business, collected U.S. dollars in cash from third parties in the United States and delivered that cash to a WLV patron who could not otherwise access cash in the U.S. The patron then electronically transferred the equivalent value of foreign currency from the patron’s foreign bank account to a foreign bank account designated by the money processor. The WLV patron paid the money processor a percentage of the value transferred. Like Human Head gambling, WLV knowingly allowed this form of gambling without scrutinizing the source of funds and without reporting the suspicious activity.

WLV also facilitated the international transfer of money and conducted other financial transactions for WLV patrons whose activity should have triggered the filing of Suspicious Activity Reports. For example, in 2018, WLV facilitated financial transactions worth approximately $1.4 million for an individual who two years earlier had been publicly linked to proxy gambling and a year earlier, while in the company of the President of Marketing of a WLV international affiliate, was denied entry to the United States because of suspected associations with a criminal organization.

In another instance, WLV allowed and did not report transactions involving millions of dollars by an individual who, according to publicly available information, had spent six years in prison in China for conducting unauthorized international monetary transactions and violations of other financial laws.

“Federal laws that regulate the reporting of financial transactions are in place to detect and stop illegal activities. Deliberately avoiding Bank Secrecy Act requirements is a form of money laundering. IRS Criminal Investigation is committed to following the money and enforcing these laws, wherever it leads” said Carissa Messick, Special Agent in Charge for IRS-CI in Las Vegas.

“Law enforcement put their collective authorities together to ensure the integrity of our financial systems and that they are not circumvented,” said DEA Special Agent in Charge Brian Clark.

As part of this investigation, 15 other defendants previously have admitted money laundering, unlicensed money transmitting, or other crimes, with associated criminal penalties of over $7.5 million.

This case was prosecuted by Assistant U.S. Attorneys Mark W. Pletcher and Carl F. Brooker IV.

Chinese Flying Money: the secret key to China’s international trading success | Journalismfund Europe

2019-06-07

WINDHOEK - The single greatest obstacle that law enforcement officials have in combatting wildlife crime and related smuggling is the lack of a money trail that can be used as evidence in court to secure convictions against the key organisers of such transactions.

This project exposes the key, enabling financial mechanism deployed by the local poaching and Chinese smuggling syndicates known as "Chinese Flying Money" or "Fei Qian", an ancient trade-based settlement system that operates outside of the overview of the international regulatory oversight of the formal banking system.

The investigation followed the trail of abalone smuggled via Namibia from the Western Cape in South Africa to Hong Kong and the New Territories, illegally harvested rosewood from Angola, Zambia and the DRC sent to China and Vietnam, as well as examining the drugs-for-abalone trade in the Western and a tax fraud case in Namibia to illustrate how the Fei Qian mechanism works.

The investigation drew on sources in Spain, Hong Kong, Namibia and South Africa, ongoing and old court cases, property, company and other public records and interviews with former and current law enforcement officials to set out the politically enabling mechanism and the means by which billions of dollars are illegally but invisibly exported from Africa to China.

----

Two previous members of the team from Spain and Hong Kong withdrew from the investigation due to changes in personal circumstances.

John Grobler

John Grobler is a seasoned investigative reporter based in Windhoek, Namibia.

Alex Hofford

Alex Hofford is a wildlife campaigner for WildAid, an NGO that focuses on reducing demand for endangered species.

need resources for your own investigative story?

Journalismfund Europe's flexible grants programmes enable journalists to produce relevant public interest stories with a European mind-set from international, national, and regional perspectives.

support independent cross-border investigative journalism

We rely on your support to continue the work that we do. Make a gift of any amount today.

Comments

Post a Comment